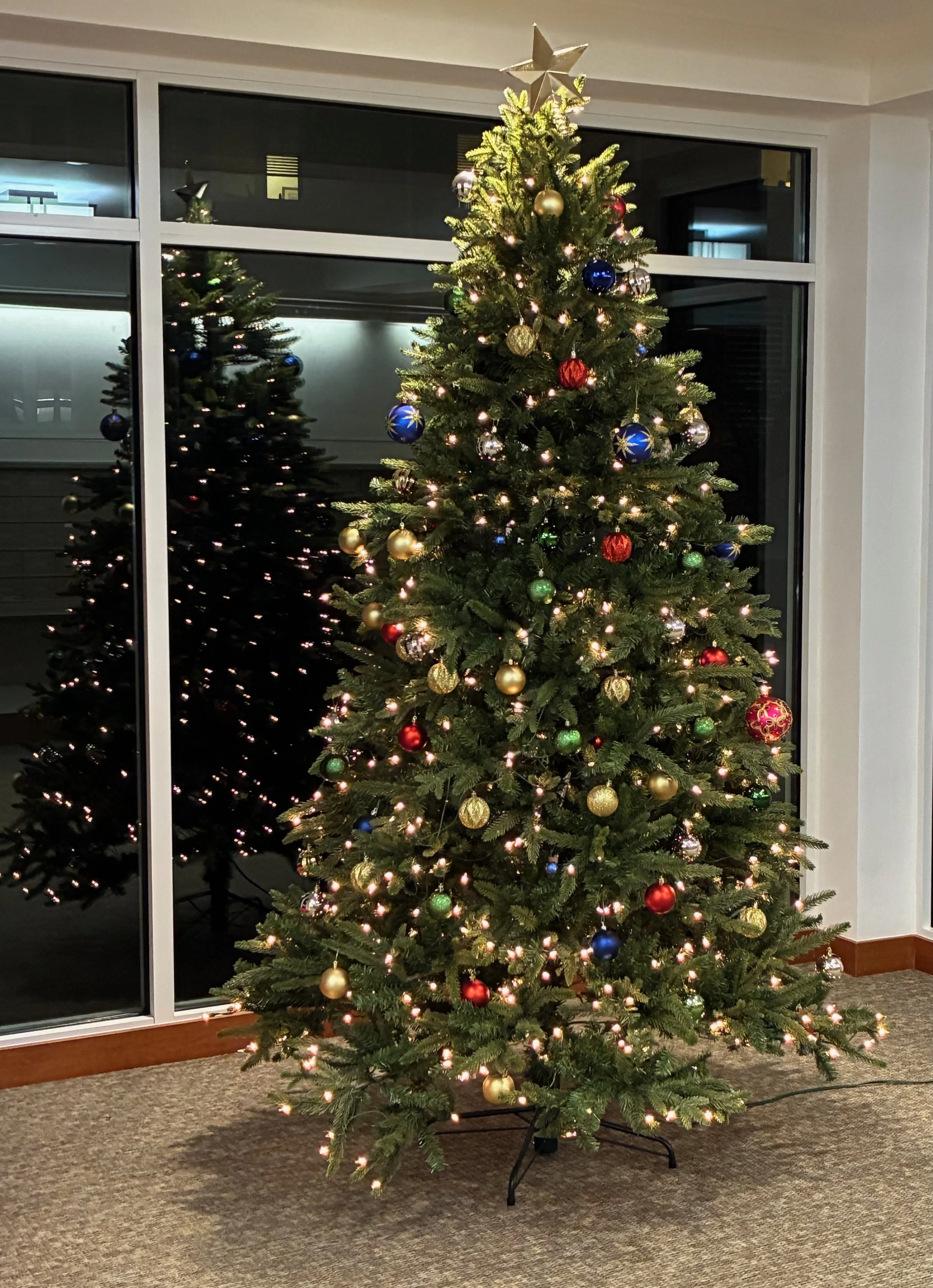

It’s a Lyndhurst Christmas!

Recently, Amanda Slattery and Cynthia Ferguson took a quick drive over to Lyndhurst to indulge in the mansions festive decorations—with 50 uniquely designed trees throughout.

Lyndhurst interior photos by Amanda Slattery

Recently, Amanda Slattery and Cynthia Ferguson took a quick drive over to Lyndhurst to indulge in the mansions festive decorations—with 50 uniquely designed trees throughout.

Lyndhurst interior photos by Amanda Slattery

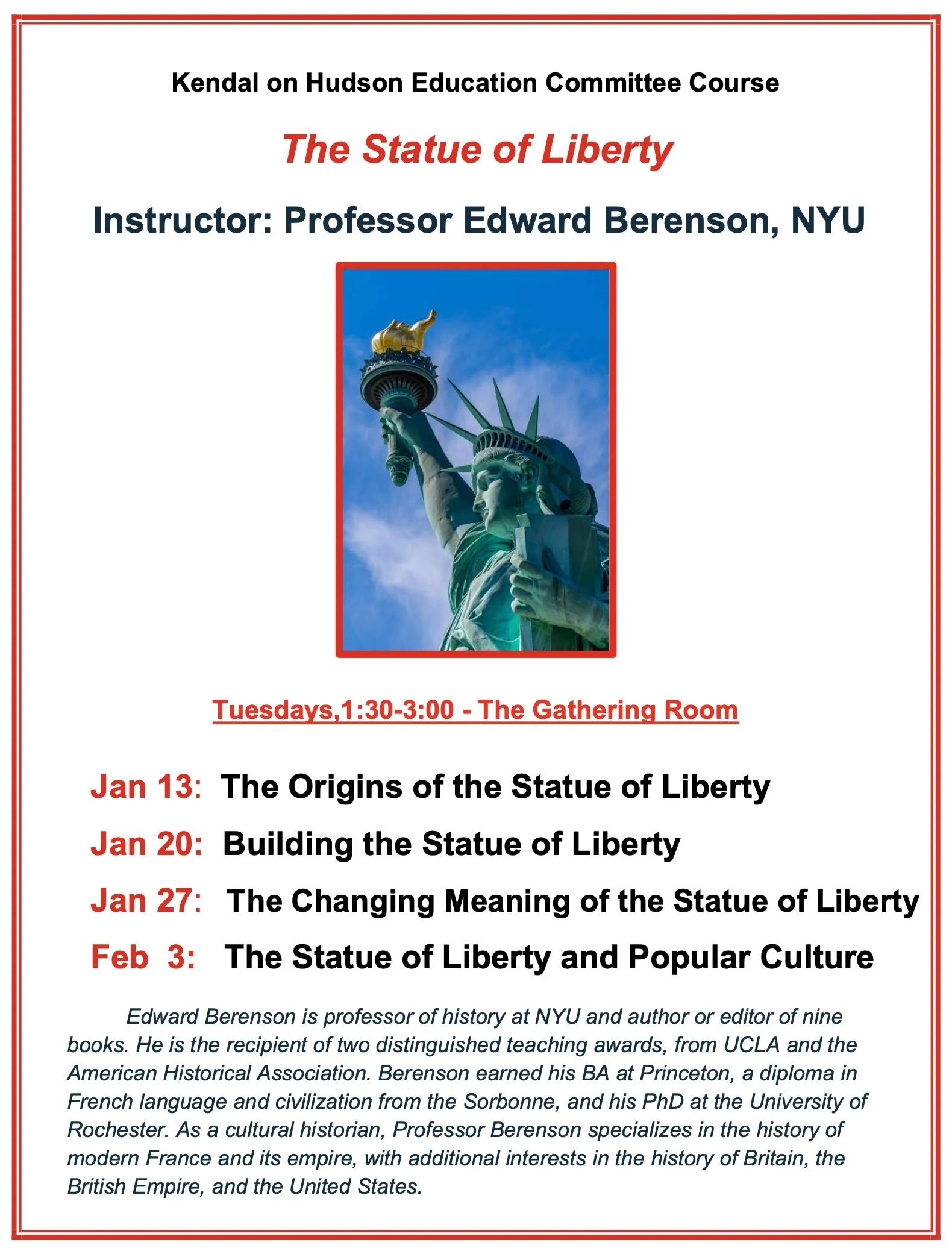

The flyer for signing up for this course has already gone into our cubbies. Missing yours but interested in signing up? You’ll find additional flyers in the Activities Alcove between the Bistro Lounge and the Gathering Room. Don’t dawdle! Sign up soon!

Photo by The Hudson Independent

The Hudson Independent published a lengthy article in their December 2025 issue on food insecurity in Westchester County, mentioning the efforts of community groups to help fill the growing void. Front and center comes our very own Pam Mitchell, thusly:

“Meanwhile, many residents in the area, such as Pam Mitchell of Sleepy Hollow, are lending a hand and bagging groceries for those in need.

As a volunteer with the Community Food Pantry of Sleepy Hollow/Tarrytown, Mitchell noticed there was a shortage of grocery bags for families when they came to collect their food.

Mitchell, a resident at the Kendal on Hudson senior living community, connected with other women to collect bags that could be reused and redistributed at the pantry. At one dropoff, more than 100 bags were donated.”

Yay, Pam!

Performances—musical, educational, edificational, just for kicks—provide a lot of enjoyment here at Kendal. Every once in a while, a photographer here can capture an extra something special, as well.

Waiting in the Wings: 15-year-old violinist Nickita Zhang performed with her older sister on the piano. Photo by Carolyn Reiss

A Family Affair: Tom Frieden—who keeps us abreast of the state of health home and abroad—with mom Nancy Frieden of Kendal fame. Photo by Edward Kasinec

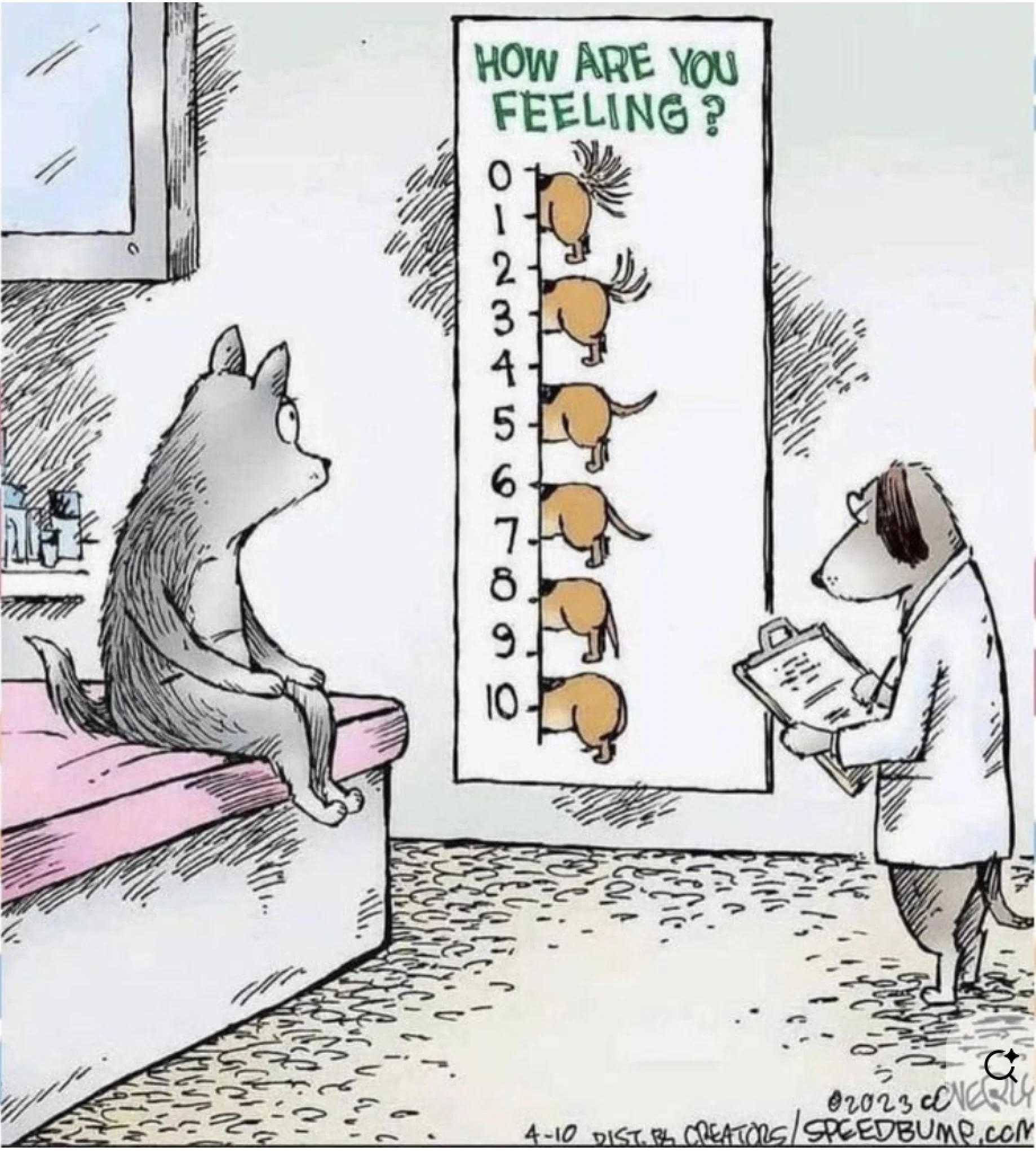

A vulture carrying two dead raccoons boards an airplane. The stewardess looks at him and says, “I’m sorry, sir, only one carrion allowed per passenger.”

Two fish swim into a concrete wall. One turns to the other and says, “Dam!”

Two Eskimos sitting in a kayak were chilly, so they lit a fire in the craft. Unsurprisingly, it sank, proving once again that you can’t have your kayak and heat it too.

Two hydrogen atoms meet. One says, “I’ve lost my electron.” The other says, “Are you sure?” The first replies, “Yes, I’m positive.”

Did you hear about the Buddhist who refused Novocain during a root-canal? His goal: transcend dental medication.

There was the person who sent 10 puns to friends, with the hope that at least one of the puns would make them laugh. No pun in ten did.

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

From the Office of Ellen Ottstadt

Although Thomas Edison was awarded 2,332 worldwide patents as an inventor, one of his lasting contributions to modern society was not proprietary: the job interview.

Edison was not just a prolific inventor—he was also a businessman in charge of an industrial empire. His corporation, Thomas A. Edison, Inc., employed more than 10,000 workers at dozens of companies. Edison wanted employees who could memorize large quantities of information and also make efficient business decisions. To find them, he devised an extensive questionnaire to assess job candidates’ knowledge and personality.

Edison began using tests for candidate assessment in the late 19th century, but the questions he asked then were very specific to open positions he needed filled. Over time, he expanded on the idea, including questions that were not directly related to the job. While interviewing research assistants, for example, Edison served them soup to see if interviewees would season the soup before they tasted it; those who did were automatically disqualified as it suggested they were prone to operate on assumptions.

In 1921, Edison debuted the Edison Test, a knowledge test with more than 140 questions. Questions varied depending on the job position, but all interviewees were asked about information outside of their areas of expertise. The queries ranged from agricultural in nature (“Where do we get prunes from?”) to commercial (“In what cities are hats and shoes made?”) to the macabre (“Name three powerful poisons.”). After a copy of the questionnaire was leaked to The New York Times, Edison had to change the question bank multiple times to ensure applicants took the exam without any outside assistance.

A score of 90% was required to pass, and out of the 718 people who had taken the test as of October 1921, only 32 (just 2%!) succeeded. The test was difficult, to say the least. Edison’s own son Theodore failed it while a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). More famously, Albert Einstein failed the exam because he forgot the speed of sound.

The 1920s saw an upswing in college-educated people in the workforce, leading to increased competition for skilled labor, and thus more applicants for employers to choose from. Edison’s strategy of questioning candidates to assess their personality and aptitude was innovative at the time, and is still standard practice today—though employers are more likely to ask about someone’s greatest accomplishment than the origins of prunes.

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

As a grownup, Bessie could have all the pets she wanted

The Ark was late, the passengers were late, and the forecast called for heavy rain

Ms. Garsh’s personal essay class was clear on day one: EVERYBODY has a story

Once again, Cornelia vowed to replace her ancient GPS

Sobekneferu had always been a winner: first, the grade-school jacks champion, and then the first female pharaoh

Art and photos by Jane Hart

Art and photo by Sheila Benedis

Photo by Maria Harris

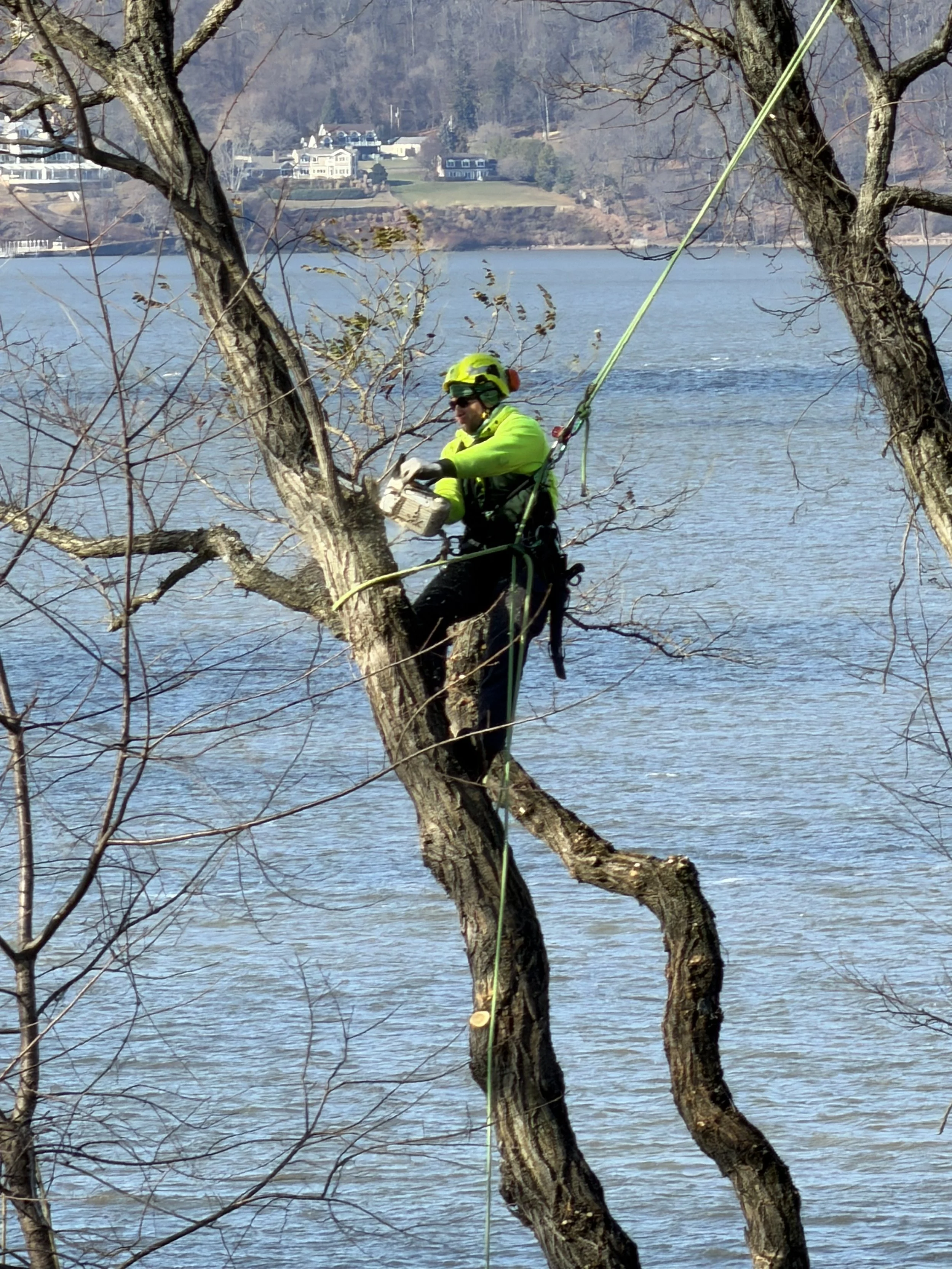

Photos by Ed Lannert

Photo by Peter Sibley

Those in the know are scratching their heads. Two of Robert Fulton’s main puzzlers were exercising body in the Fitness Center rather than brain at the puzzle table. Very puzzling . . .

Photo by Cathie Campbell

Photo by Edward Kasinec

Recently, Kendalites traveled to Asia-on-the-Hudson, aka The Asia Society, where a docent-led tour covered some of the groundbreaking exhibitions of the art of Asia and Asian diasporas.

Photos by Harry Bloomfeld

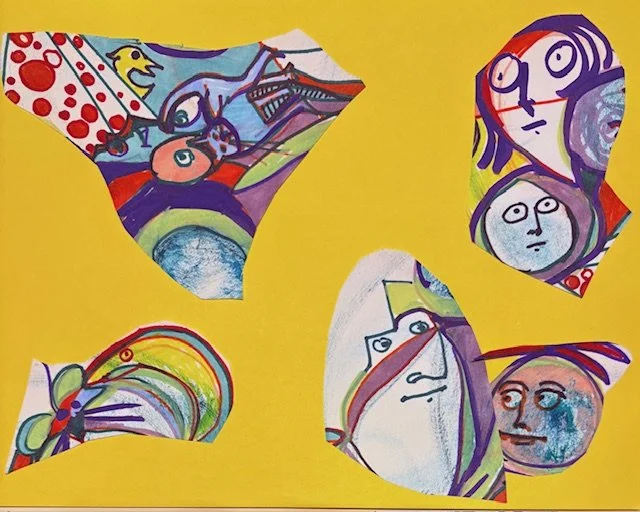

Last week, we included pictures of landscapes and such that Lynn Brady took recently on a trip to Spain. This week, we’ve included some of the pictures she took of interiors.

Dali art

Dali art

A rehearsal in the Catalan Music Hall

Gaudi design at the Catalan Music Hall

In the interior of the Parc Guell

Photos by Lynn Brady

I wondered why the baseball kept getting bigger. Then it hit me.

A sign on the lawn at a drug rehab center said: “Keep off the Grass.”

If you jumped off the bridge in Paris, you’d be in Seine.

A backward poet writes inverse.

In a democracy, it’s your vote that counts. In feudalism, it’s your count that votes.

When cannibals ate a missionary, they got a taste of religion.

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

To Be Continued

From the Office of Ellen Ottstadt

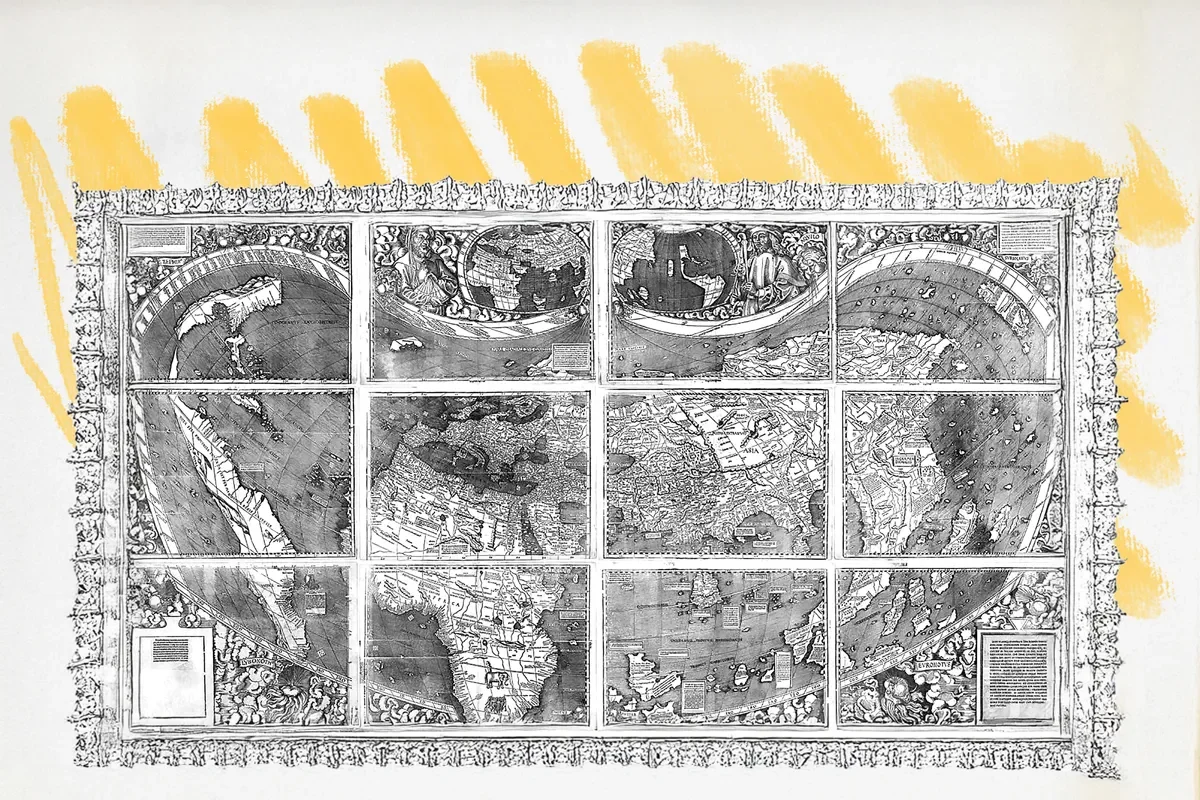

In 1507, a group of scholars in the small French town of Saint-Dié published a world map that changed how Europeans saw the globe—and gave “America” its name. Created by German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller and scholar Matthias Ringmann, the map was the first to show the New World as a separate continent, surrounded by ocean, rather than as part of Asia.

The two men drew on Portuguese nautical data and letters attributed to Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci to create the map. Though it later emerged they were doctored, the letters appeared to argue that Vespucci had found an entirely new landmass, not the eastern edge of Asia, as Christopher Columbus believed. Waldseemüller and Ringmann agreed with this idea—and in an accompanying book, Cosmographiae Introductio, they proposed naming this “fourth part” of the world “America,” after Vespucci’s Latinized first name, Americus.

Though Waldseemüller later dropped the name from his maps, others embraced it. When cartographer Gerardus Mercator applied the name “America” to the entire Western Hemisphere in 1538, it quickly became standard.

Only one copy of Waldseemüller’s 1507 map survives today—discovered in a German castle in 1901 and now housed at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Sometimes called “America’s birth certificate,” it marks the moment when a new name —and a New World—entered the map of human understanding.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Mimi Abramovitz

© Kendal on Hudson Residents Association 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 all rights reserved. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Photographs of life at Kendal on Hudson are by residents.