Contributed by Donald Butt

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

Contributed by Donald Butt

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

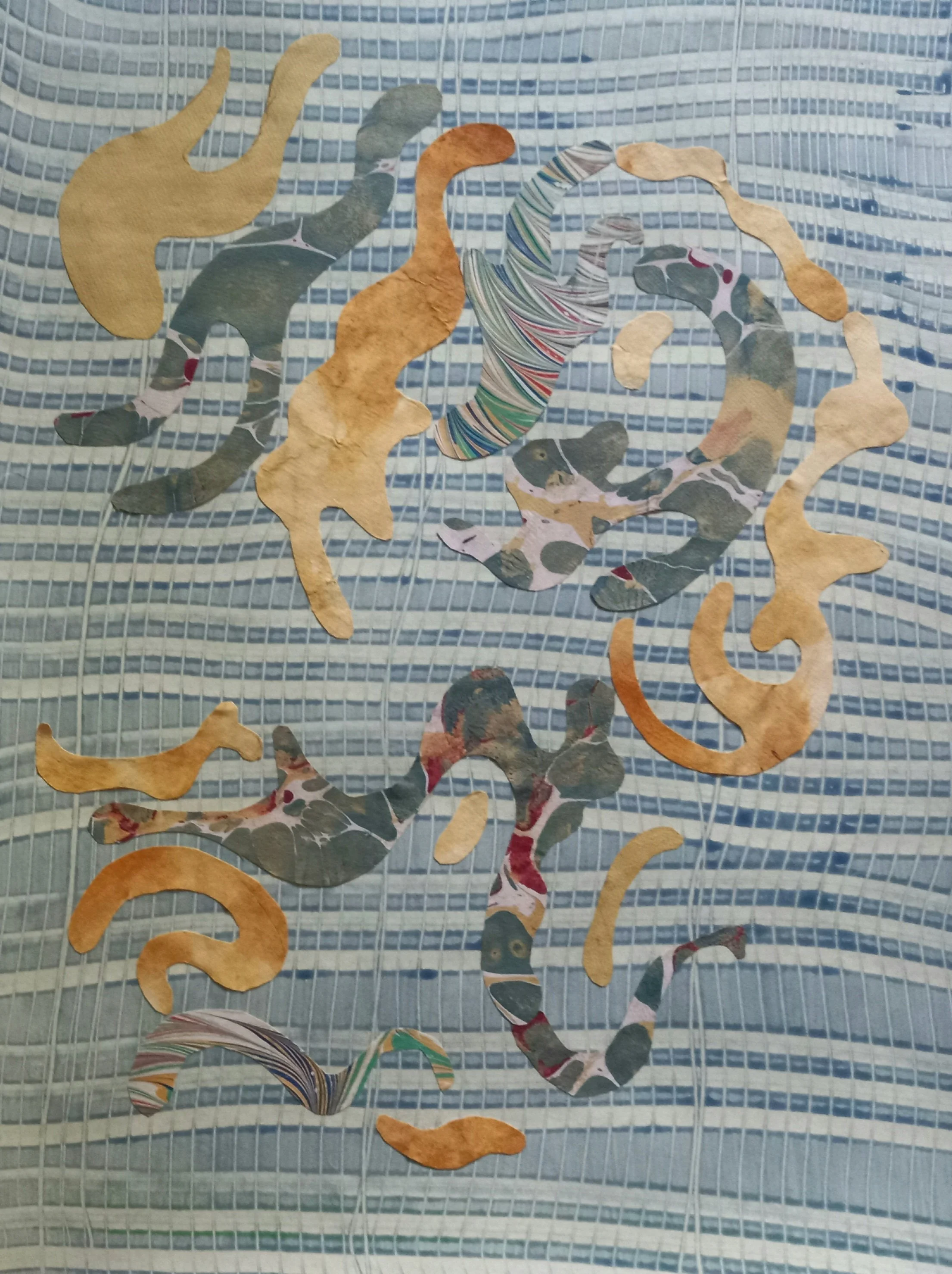

Art and photo by Sheila Benedis

Each week, Muriel Fox makes copies of Spotlight for our community. She’s rather caught there because the copier can be finicky. So, time well spent: with the Times.

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

A new fountain now graces the Clearwater garden, following the retirement of the former fountain that had been—appropriately—feeling its age.

Photo contributed by Ellen Ottstadt

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

Photo by Edward Kasinec

Bee’s eye view, by Ed Lannert

Late Hibiscus in the Healing Garden, by Sue Bastian

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

Recently, Kendalites visited Stonecrop Gardens for a tour of their vast and wonderful gardens. Here’s just a taste:

Photos by Harry Bloomfeld

Autocorrect—we love it and hate it:

We’ll, we’ll, we’ll . . . if it isn’t autocorrect.

Autocorrect can go straight to he’ll.

Autocorrect has become my worst enema.

I tried to say, “I’m a functional adult,” but my phone changed it to “fictional adult,” and I feel like that’s more accurate.

Thanks to autocorrect, 1 in 5 children will be getting a visit from Satan this Christmas.

The guy who invented autocorrect for smartphones passed away today. Restaurant in peace.

Contributed by Joe Bruno

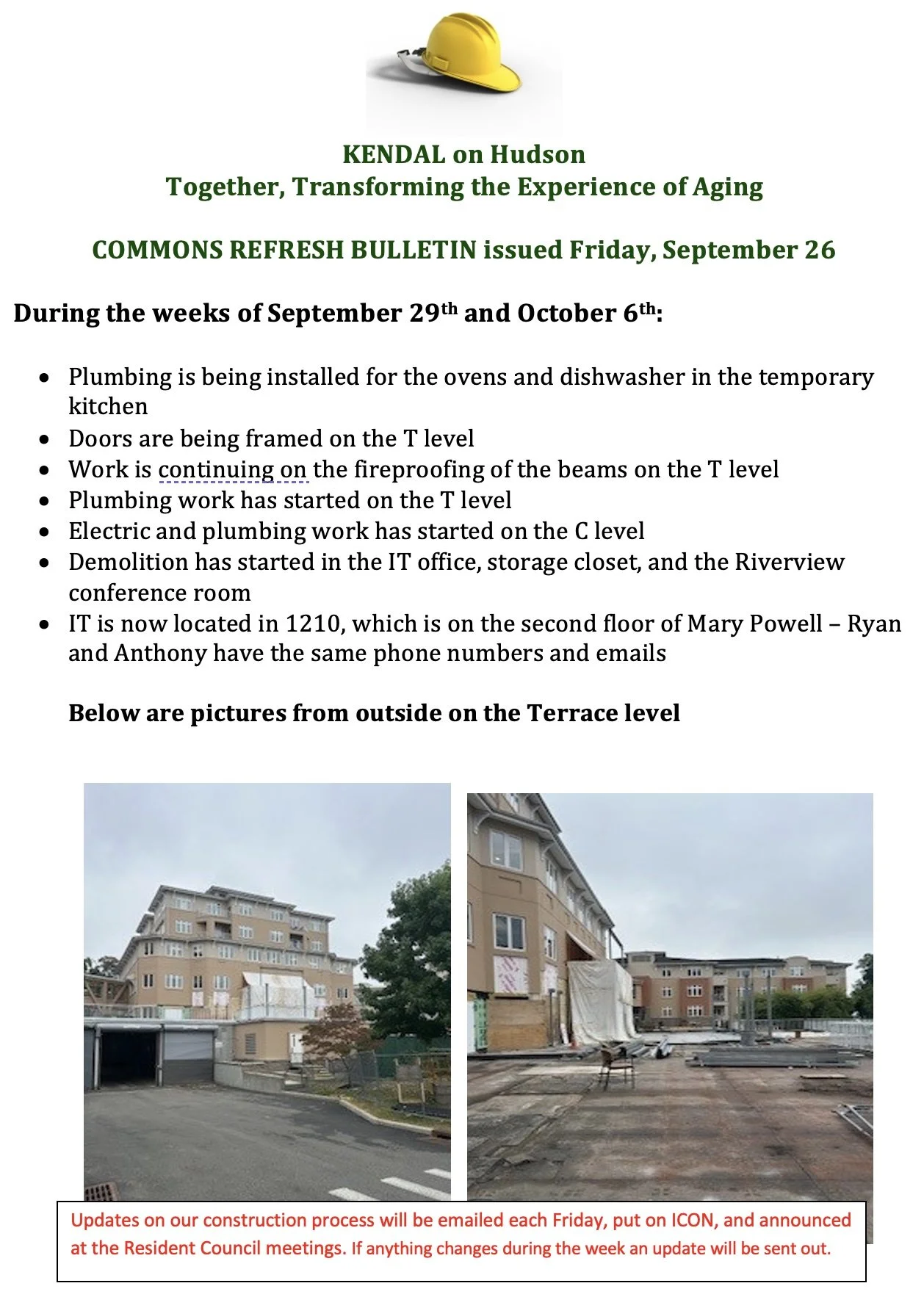

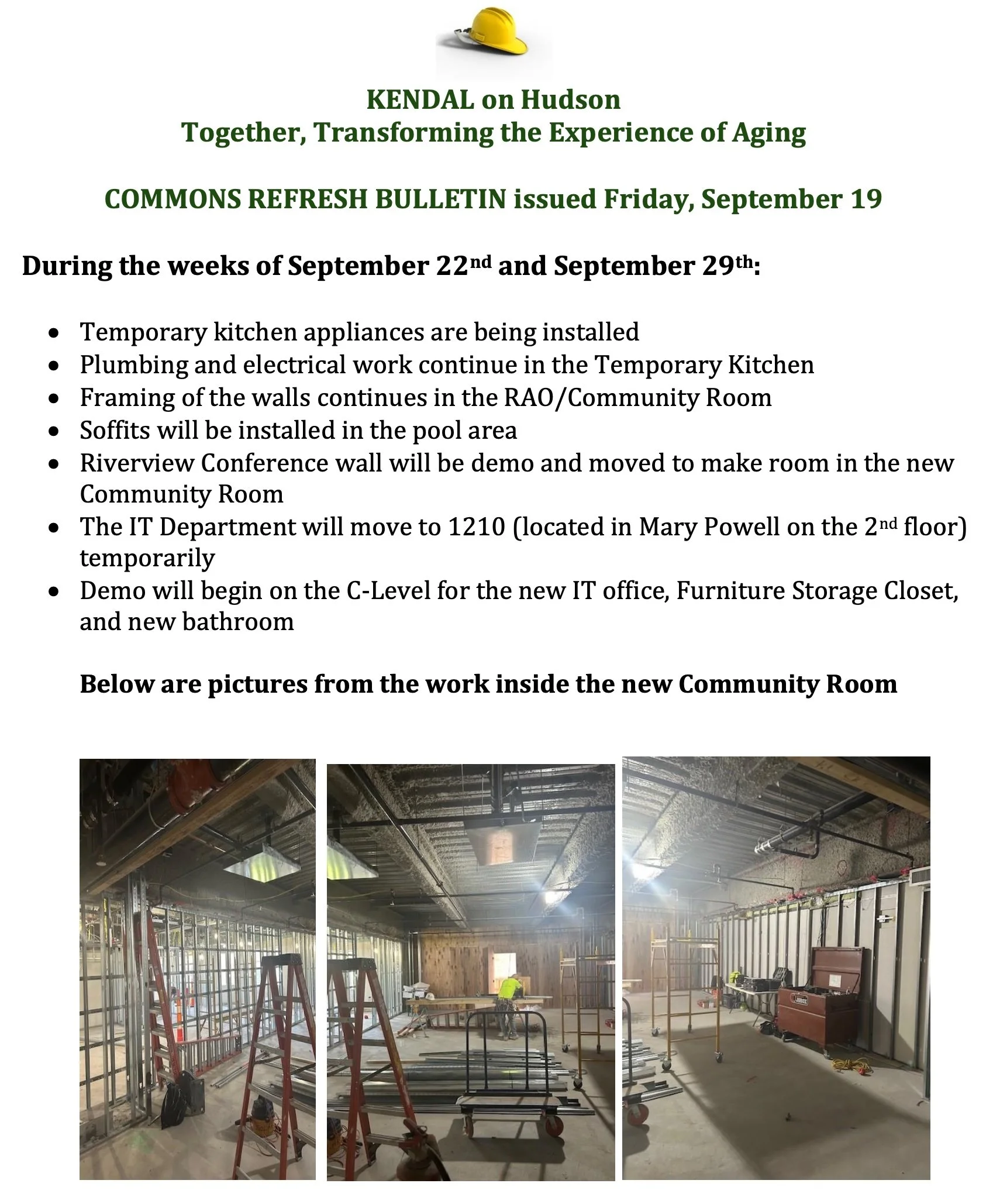

From the Office of Ellen Ottstadt

From the Office of David Pojman

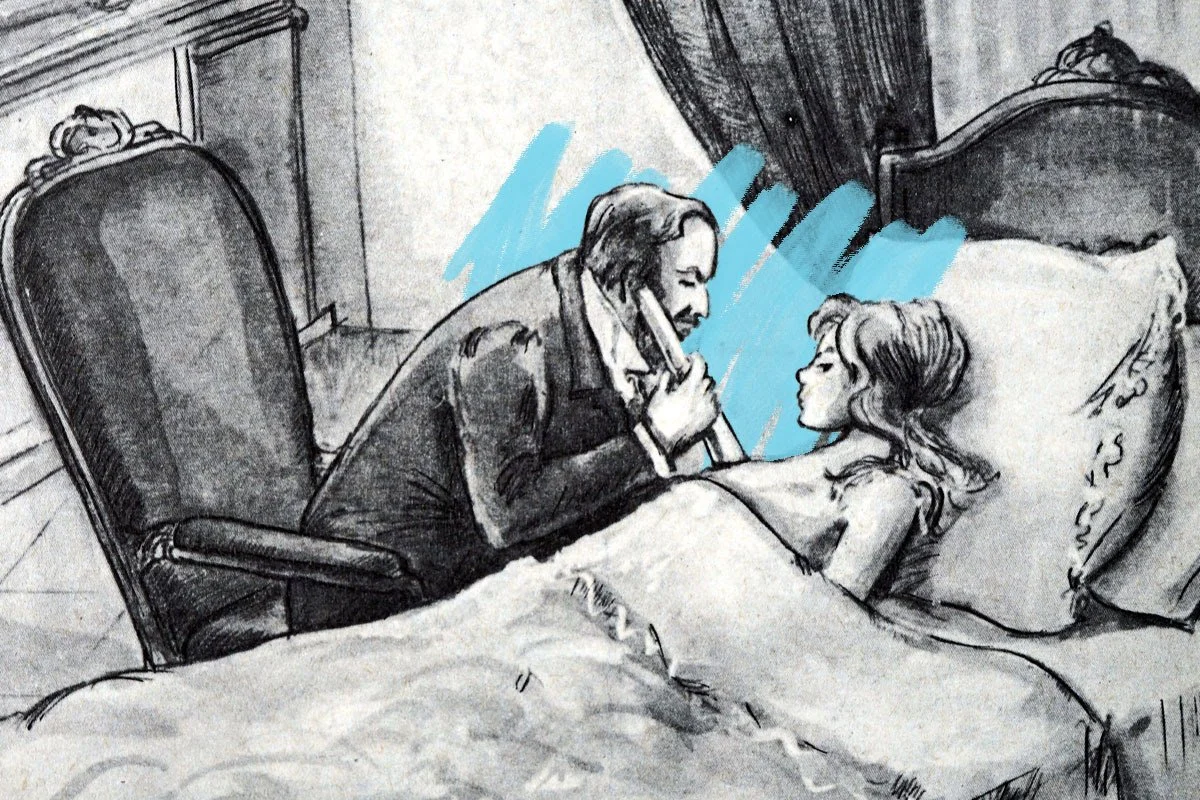

In 1816, a French physician named René Laennec found himself in a delicate situation. He needed to listen to the heart of a young female patient but didn’t have an ideal way to do so based on the standard practices of the time. Doctors in the early 19th century relied primarily on touch to assess the heart, pressing their hands to gauge its strength and rhythm. This method often wasn’t reliable, especially, as was the case in Laennec’s situation, if the patient was of a heavier weight. Applying the ear directly to a chest was another approach, but Laennec felt that would be inappropriate and uncomfortable given his patient’s age and gender.

Laennec also happened to be a skilled musician. Drawing on a basic principle of acoustics—that sound travels better through solid materials than through air—he rolled a sheet of paper into a cylinder and placed one end on the patient’s chest and the other to his ear. The heartbeat came through far more clearly and distinctly than it would have with touch or direct ear contact. Three years later, he published his findings and the first design of a monaural stethoscope, the name of which comes from the Greek words stethos, meaning “chest,” and skopein, meaning “to explore.”

The device was a simple wooden tube about 10 inches long that carried sound to one ear. The stethoscope marked the start of mediate auscultation—diagnosing conditions by listening to the body’s internal functions. Laennec’s design was used until flexible rubber-tubed binaural models appeared later in the 19th century.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Jane Hart

Contributed by Donald Butt

Contributed by Barbara Bruno

Sid and Griffin were inseparable

The Met’s new Saturday soap-opera series broadcast directly to Lena’s Laundromat

They met on the 7:00 am lizardboat—and the rest is history

It was adorable to hear the little ones mimic the politicians on TV

Bobo couldn’t get enough Great Aunt Bunni stories

Art and photos by Jane Hart

Art and photo by Sheila Benedis

Photo by Cynthia Ferguson

Photo by Harry Bloomfeld

Copland House Ensemble Concert, September 14, photo by Ed Lannert

Photo by Joe Bruno

Photos by Carolyn Reiss

Loose again Tuesday morning! Seems in the herd this year there are more curious youngsters than usual. Oh, this younger generation!

Which led to an unusual meeting: Allie Reiss and Billy Goat. Neither seemed concerned . . .

Photos by Carolyn Reiss

Photo by Barbara Wallach

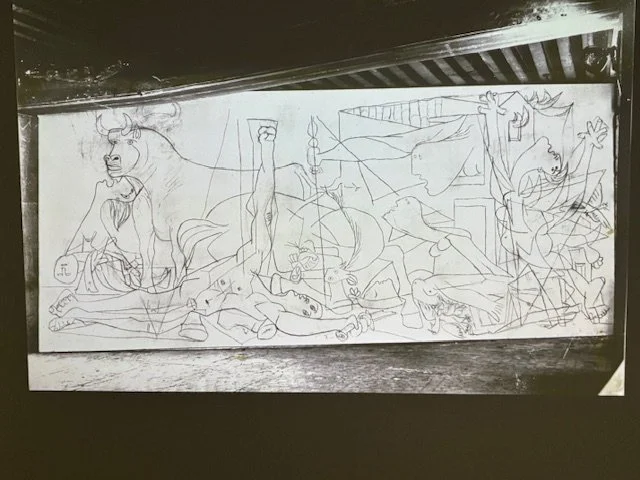

Pat McGrath spent the last few weeks bicycling with his daughter through the hills and dales of Italy and France, and visiting friends in Paris. He sent lovely pictures of the surrounding landscapes and cityscapes. And a bonus, too.

Porto Vecchio, Corsica

Levie, Corsica

Sartene, Corsica

Bonifacio, Corsica

First sketch of Guernica, Picasso Museum, Paris

Eifel Tower at dusk

Gallery at Chenonceaux

St. Romain sur Cher, France

And now the bonus . . .

That’s right: a picture of goats! French goats! And direct from Couddes.

A big red ship has been hanging out for several days on the Hudson River—right in our sight line. What is that thing doing? Two weeks ago, we published the information Joe Bruno found to answer that question: it’s a cable-laying ship, laying a cable beneath the Hudson. And now—as is the Residents Website tradition of providing breaking-news—Joe has come up with even more information!

Want to know more (note: pictures are included)? Click below.

Black Cohosh in Rockwood, photo by Harry Bloomfeld

Garden Dahliah, photo by Harry Bloomfeld

A “Next” of Mushrooms, photo by Rich Dooley

Common Ivy . . . and Friend, photo by Harry Bloomfeld

Herbst’s Bloodleaf, photo by Harry Blooomfeld

From the office of Ellen Ottstadt

Margaret Ann Roth recently provided a compendium of, well, discrete observances on our world, age, and philosophy. They are both thought-provoking and insightful. We offer a few below in Part II of this discussion of life:

Author, author! That would be Mimi Abramovitz whose latest edition of Regulating the Lives of Women: Social Welfare Policy from Colonial Times to Present is just being released in its Fourth—count ‘em: four—edition. Used widely in Women’s Studies and American History courses, the flyer below tells you everything you might want to know about this soon-to-be available tome of renown.

Designing a yearly calendar is tricky, since solar days, lunar months, and solar years don’t completely line up. The Gregorian calendar, established by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and used today throughout the Western world, aligns calendar dates with the seasons by splitting a solar year into 12 parts—not tied to the cycles of the moon—and adding an extra day every four years (with some exceptions). But making the switch to this calendar from its predecessor, the ancient Julian calendar, led to some clunky timekeeping—such as Britain skipping a whole 11 days in September 1752.

Because the Julian calendar under-calculated a solar year by roughly 11 minutes, it gradually got out of sync with the actual seasons. The discrepancy wasn’t noticeable at first, but by Gregory XIII’s papacy in the 16th century, Easter had drifted 10 days from the date the Catholic Church intended it to be celebrated. To remedy this, the pope adjusted the leap day formula and anchored the calendar by tying March 21 to the spring equinox.

Catholic-dominant areas of Europe, such as Italy, adopted the adjusted calendar within a year, and the rest of Europe eventually followed suit, albeit some countries more slowly than others. Britain, for instance, waited nearly 200 years to make the switch, and by that time, the two calendars were 11 days out of sync. In order to align with the Gregorian calendar, Britain skipped 11 days in the year 1752, following September 2 with September 14.

Before Britain implemented the Gregorian calendar, the new year started on March 25. The first New Year’s Day on January 1 was in 1752, but because the previous year still started on March 25, 1751 ended up being only 282 days long—the shortest year in English history. Interestingly, the tradition of beginning the year in March hasn’t completely disappeared: Even today, tax years in the U.K. start in the spring.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Jane Hart

© Kendal on Hudson Residents Association 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022 all rights reserved. Please do not reproduce without permission.

Photographs of life at Kendal on Hudson are by residents.