From the office of Ellen Ottstadt

Understanding Life . . .

Margaret Ann Roth recently provided a compendium of, well, discrete observances on our world, age, and philosophy. They are both thought-provoking and insightful. We offer a few below in Part II of this discussion of life:

Coming Soon to a Library Near You: Kendal's

Author, author! That would be Mimi Abramovitz whose latest edition of Regulating the Lives of Women: Social Welfare Policy from Colonial Times to Present is just being released in its Fourth—count ‘em: four—edition. Used widely in Women’s Studies and American History courses, the flyer below tells you everything you might want to know about this soon-to-be available tome of renown.

I Never Knew That

Britain Once Skipped 11 Days in September

Designing a yearly calendar is tricky, since solar days, lunar months, and solar years don’t completely line up. The Gregorian calendar, established by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and used today throughout the Western world, aligns calendar dates with the seasons by splitting a solar year into 12 parts—not tied to the cycles of the moon—and adding an extra day every four years (with some exceptions). But making the switch to this calendar from its predecessor, the ancient Julian calendar, led to some clunky timekeeping—such as Britain skipping a whole 11 days in September 1752.

Because the Julian calendar under-calculated a solar year by roughly 11 minutes, it gradually got out of sync with the actual seasons. The discrepancy wasn’t noticeable at first, but by Gregory XIII’s papacy in the 16th century, Easter had drifted 10 days from the date the Catholic Church intended it to be celebrated. To remedy this, the pope adjusted the leap day formula and anchored the calendar by tying March 21 to the spring equinox.

Catholic-dominant areas of Europe, such as Italy, adopted the adjusted calendar within a year, and the rest of Europe eventually followed suit, albeit some countries more slowly than others. Britain, for instance, waited nearly 200 years to make the switch, and by that time, the two calendars were 11 days out of sync. In order to align with the Gregorian calendar, Britain skipped 11 days in the year 1752, following September 2 with September 14.

Before Britain implemented the Gregorian calendar, the new year started on March 25. The first New Year’s Day on January 1 was in 1752, but because the previous year still started on March 25, 1751 ended up being only 282 days long—the shortest year in English history. Interestingly, the tradition of beginning the year in March hasn’t completely disappeared: Even today, tax years in the U.K. start in the spring.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Jane Hart

For Your Funny Bone

Contributed by Barbara Bruno

Contributed by Barbara Bruno

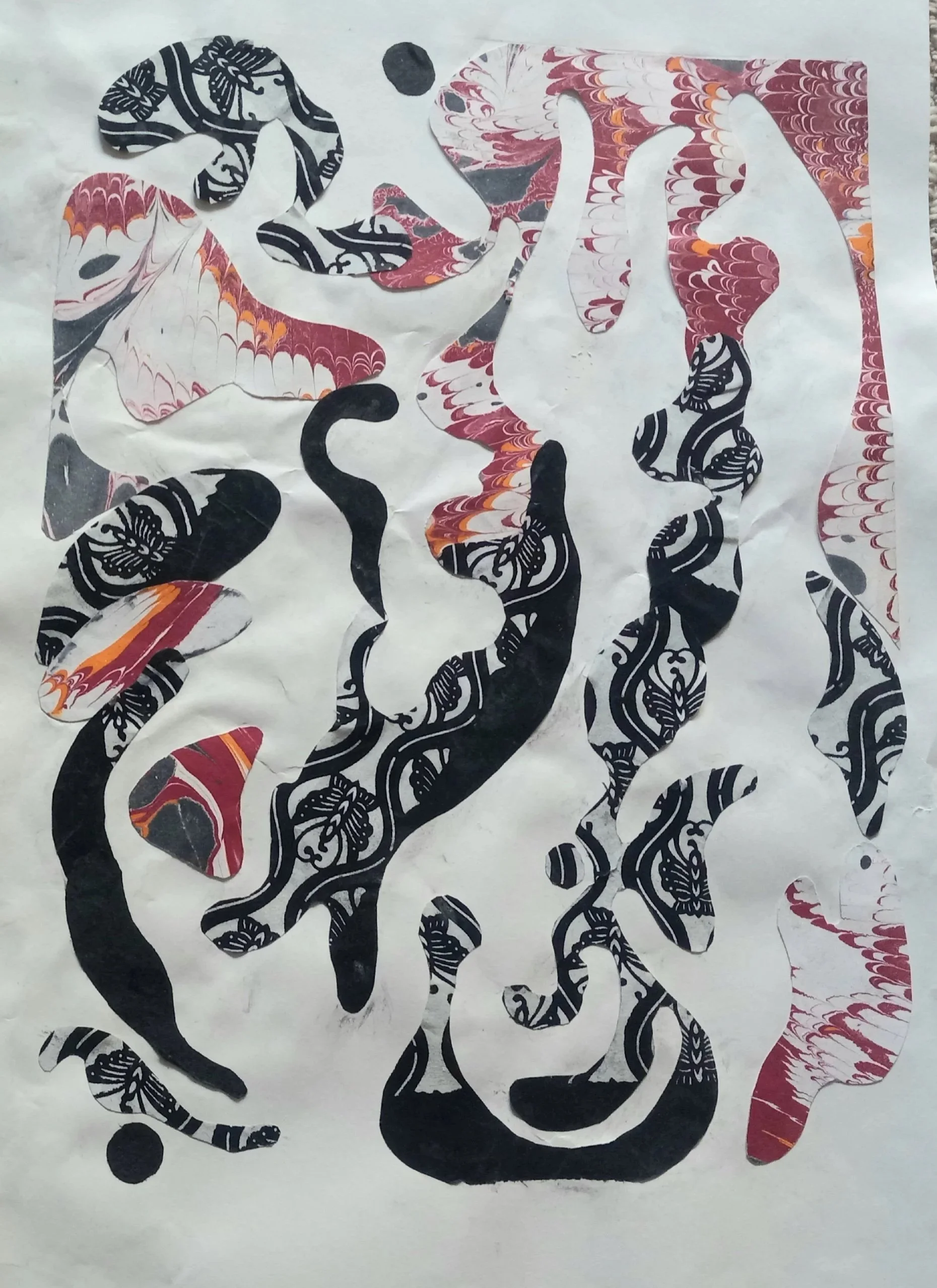

Drawing with Scissors VI, by Sheila Benedis

Art and photo by Sheila Benedis

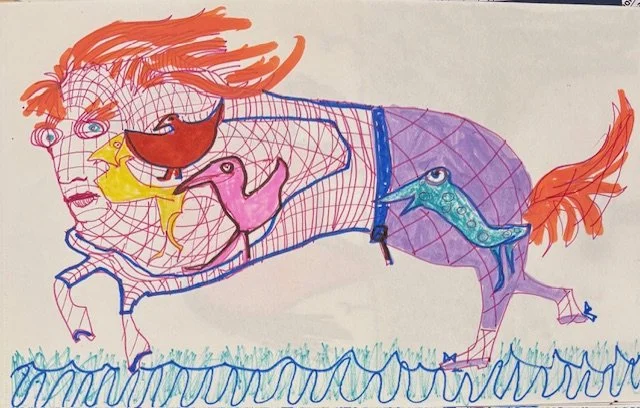

Art by Hart

Orange Julius liked to squeeze in one last game of golf

Gracie was nice to drill Casey on his Latin verbs

Piano-tuning was more complicated than Simeon thought

Molly’s mesh suit was annoying, but it kept shore birds from crashing into her

The second act-lovers’ duet from inside a giant dolphin always brought the house down

Art and photo by Jane Hart

In and Around Kendal

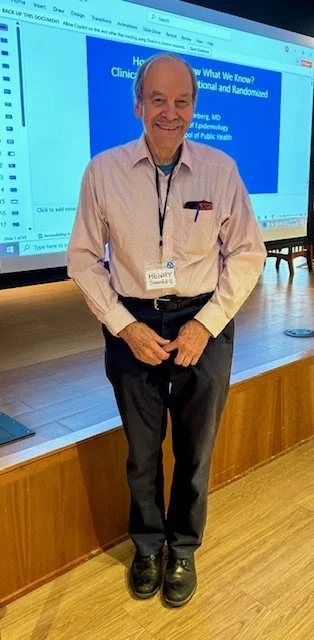

Henry Enlightens Us All

Photo by Edward Kasinec

Henry Greenberg held his audience in rapt attention as he explained the practice and process of scientific exploration in clinical trials.

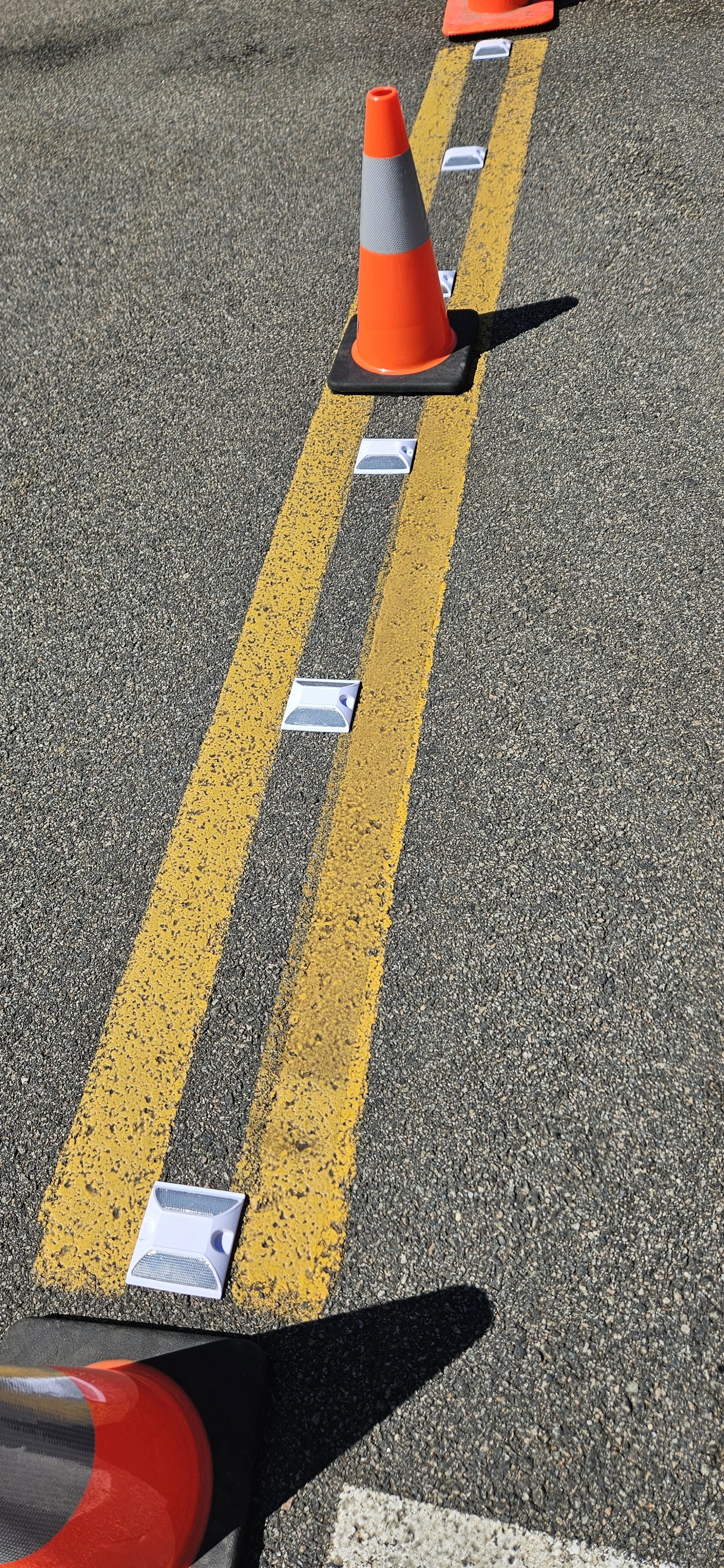

Lightening the Drive around Fulton

The night-time drive around Fulton just got easier. Traffic reflectors have been embedded in the roadway. Stay tuned for more illuminating news.

Photo by Joe Bruno

Kendal Bird Watchers Watching Bird Watcher Ann Swaim Watch Birds

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

A Lovely Day in the Park

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

Ominous

Is the world trying to tell us something?

Photo by Philip Monteleoni

Spectacular!

Photo by Amanda Slattery

Family: Bovidae, Genus: Capra, Location: Right Next Door

It’s What Goats Do—and Do So Well

“I’d climb the highest heights for you . . . “

Photo by Aruna Raghavan

Just chillin’ . . .

Photo by Aruna Raghavan

“Barking” up the right tree . . .

Photo by Edward Kasinec

“I’m Ready for My Close-up”

Photo by Carolyn Reiss

Photo by Aruna Raghavan

Photo by Ed Lannert

Understanding Life . . .

Margaret Ann Roth recently provided a compendium of, well, discrete observances on our world, age, and philosophy. They are both thought-provoking and insightful. We offer a few below:

To be continued . . .

Contributed by Margaret Ann Roth

I Never Knew That

How Did Salt and Pepper Become the Two Most Common Seasonings?

Spices have been central to human history since antiquity, influencing trade routes and economies along the way. But despite the rich array of flavors that have traveled the world, salt and pepper have emerged as the most popular seasonings in the Western world. Salt, an essential mineral, was once coveted for food preservation; pepper, a spice derived from dried peppercorn plant berries, used to be worth its weight in gold. Their popularity and ubiquitous inseparability have even led to their names being used as an adjective, as in “salt-and-pepper” hair. Here’s a look at how necessity, global trade, and culinary innovation helped salt and pepper become the two most common food seasonings.

A Dash of Salt

Salt’s journey to dinner tables is rooted in its importance to human life. The natural mineral is crucial for maintaining hydration, nerve function, and muscle control in the body, among other things. Given salt’s essential role in survival, it’s no surprise that humans developed a taste for it. Early human diets were heavy in meat and naturally provided sufficient salt. But as nomadic hunter-gatherers settled into agricultural societies and diets started including more grains, supplementing salt became important. The resource, though naturally abundant, wasn’t always easy to obtain, and it became a highly sought-after commodity throughout expanding civilizations.

In ancient Rome, the production and transport of salt evolved into a major industry. Salt was highly valued and was even used as currency, with soldiers sometimes receiving their salarium, or wages, in salt—a practice that gave rise to the English word “salary.” (Sal is the Latin word for salt.) As European empires expanded and trade routes grew, so did salt’s reach, though it largely remained a necessity of food preservation and was used as a seasoning only by the wealthy. Throughout the Middle Ages, upper-class hosts even made sure their guests of honor were seated next to elaborate, expensive salt cellars at the dining table.

A Pinch of Pepper

Around the same time, black pepper was experiencing peak popularity in medieval Europe. Native to India’s Malabar Coast, pepper was used in local cooking as early as 2000 BCE, but as trade networks expanded, the spice became highly prized in the Roman Empire, where it was as valuable as gold. Like salt, it remained a top commodity and a luxury for centuries throughout Europe due to difficulties importing it from tropical regions—as well as for its supposed medicinal properties. Black pepper was believed to aid digestion, ward off diseases, and treat ailments such as arthritis and gout.

By the mid-17th century, however, these medical beliefs were waning, and the spice trade shifted significantly as new imports such as coffee, chocolate, and tobacco entered the scene. Food preferences also changed, reflecting refinements in regional cooking, especially in France.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Jane Hart

For Your Funny Bone

Contributed by Maria Harris

Contributed by Barbara Wallach

Art by Hart

Twin puppeteers Al and Dora had their hands full

Emily carried quarters in case she saw any hungry parking meters

It was the Hendersons’ ongoing conflict: she was very sensitive to the sun, but he “needed” the beach

They’d rented a golden retriever for the first Fall meet-and-greet

Elsa June repurposed her old Venetian blinds into a cute 1920s flapper outfit

Art and photos by Jane Hart

Drawing with Tissue VIII, by Sheila Benedis

Art and photo by Sheila Benedis

In and Around Kendal

Another Beautiful Day in Rockwood

Photo by Philip Monteleoni

How to Tell It’s Friday at Kendal

Pizza, anyone?

How a City Kid Becomes a Goat Herd

Step one: Live at Kendal

Step two: Live at Kendal in the spring/summer

Step three: Live at Kendal in the spring/summer when some of the wilier goats jump the fence and lead the others to freedom

Step four: Live at Kendal in the spring/summer and take a walk in Rockwood Park when some of the wilier goats jump the fence and lead the others to freedom—as did the Abramovitz.

“Let’s get outta here!”

Discussing consequences of actions with Dr. Abramovitz.

Though city-born-and-bred, he seems a natural in goat-herding.

Photos by Mimi Abramovitz

Ya Gotta Have Faith in Rockwood Park

A praying mantis, minding his own business: praying

Having achieved his freedom, an escaped goat achieves foundation-top and pauses to kneel . . . in a prayer of thanksgiving, perhaps?

Photos by Rich Dooley

Another Beautiful Days Comes to a Lovely End

Photo by Philip Monteleoni

Out and About

A Breezy Day on the Walkway over the Hudson

Mystery Barge on the Hudson

A big red ship has been hanging out for several days on the Hudson River—right in our sight line. What is that thing doing? Joe Bruno has found the answer: it’s a cable-laying ship, laying a cable beneath the Hudson.

But what is it for? Its goal is to transport electricity from Canada to New York City.

Want to know more (note: pictures are included)? Click below.

Independent Living Ad Hoc Healthcare Committee Update: Come One, Come All to Learn

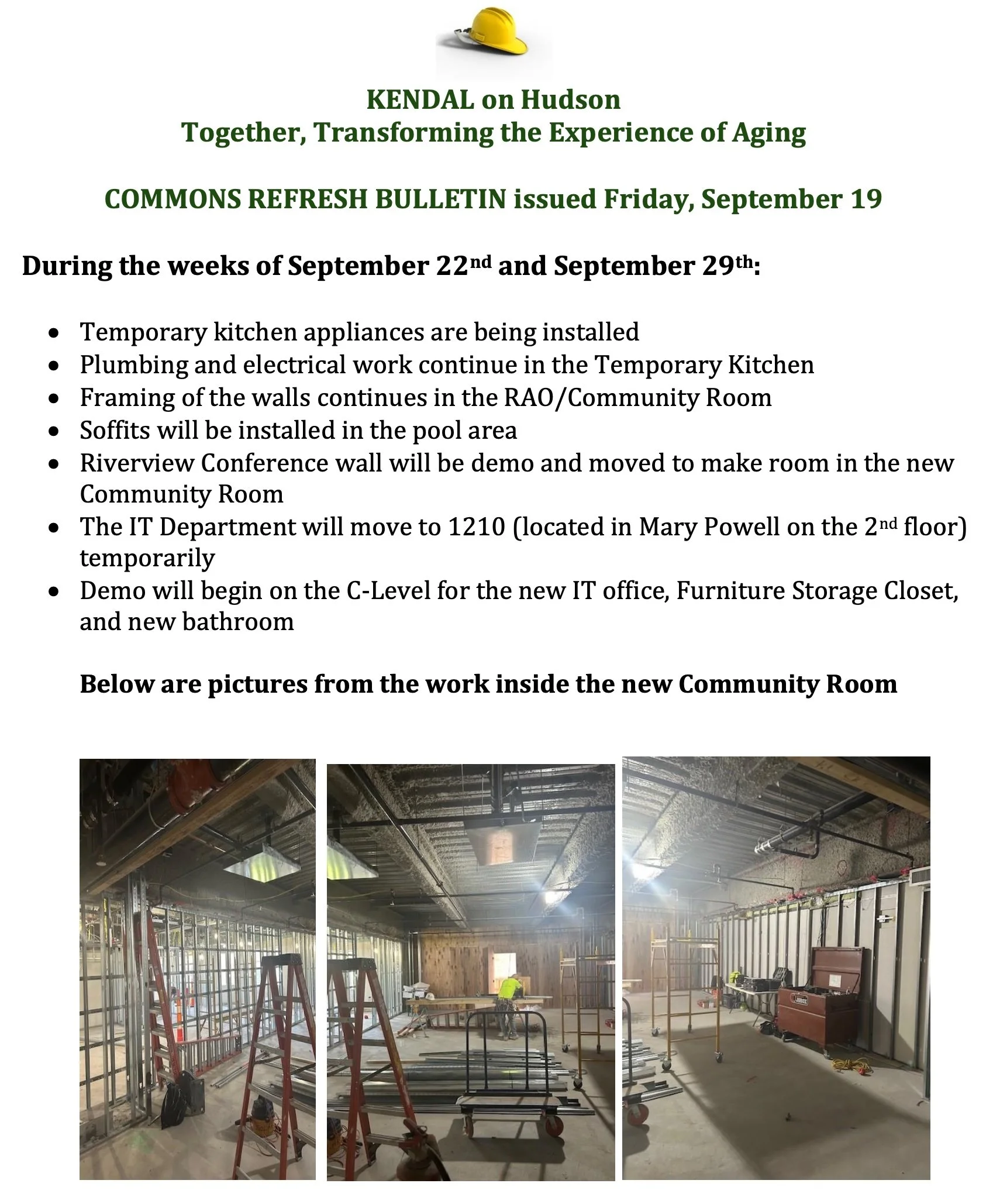

Weekly Construction Report

From the Office of Ellen Ottstadt

I Never Knew That

What Did People Use for IDs Before Photos?

Names (and the Trouble With Them)

A name was the most basic marker of identity for centuries, but it often wasn’t enough. In ancient Greece, to distinguish between people with the same first name, individuals were also identified by their father’s name. For example, an Athenian pottery shard from the fifth century BCE names Pericles as “Pericles son of Xanthippus.” In ancient Egypt, the naming convention might have reflected the name of a master rather than a parent.

But when everyone shared the same name—as in one Roman Egyptian declaration in 146 CE, signed by “Stotoetis, son of Stotoetis, grandson of Stotoetis”—things could get muddled. To resolve this, officials turned to another strategy: describing the body itself.

Scars and Silk

Detailed physical descriptions often served as a kind of textual portrait. An Egyptian will from 242 BCE describes its subject with remarkable specificity: “65 years old, of middle height, square built, dim-sighted, with a scar on the left part of the temple and on the right side of the jaw and also below the cheek and above the upper lip.” Such marks made the body “legible” for identification.

In 15th-century Bern, Switzerland, when authorities sought to arrest a fraudulent winemaker, they didn’t just list his name. They issued a description: “large fat Martin Walliser, and he has on him a silk jerkin.” Clothing—then a significant investment and deeply symbolic—became part of someone’s identifying characteristics. A person’s outfit could mark their profession, social standing, or even their city of origin.

Badges and Insignia

Uniforms and insignia served a similar function, especially for travelers. In the late 15th century, official couriers from cities such as Basel, Switzerland, and Strasburg, France, wore uniforms in city colors and carried visible badges. Pilgrims and beggars in the late Middle Ages and beyond were also required to wear specific objects—such as metal badges or tokens—that marked their status and origin. Some badges allowed the bearer to beg legally or buy subsidized bread, offering both practical aid and visible authentication.

Seals, Signatures, and Letters

Seals also served as powerful proxies for the self. From Mesopotamian cylinder seals to Roman oculist stamps and medieval wax impressions, these identifiers could represent both authority and authenticity. In medieval Britain, seals were often made of beeswax and attached to documents with colored tags. More than just utilitarian tools, seals were embedded with personal iconography and could even be worn as jewelry.

In many cases, travelers also had to carry letters from local priests or magistrates identifying who they were. By the 16th century, such documentation became increasingly essential, and failing to carry an identity paper could result in penalties. This passport-like system of “safe conduct” documents gradually started to spread. What began as a protection for merchants and diplomats evolved into a bureaucratic necessity for everyday people.

As written records became more widespread in medieval Europe, so did the need for permanent, portable identifiers. Royal interest in documenting property and legal rights led to the proliferation of official records, which in turn prompted the spread of literacy. Even as early as the 13th century in England, it was already considered risky to travel far without written identification.

The signature eventually emerged as a formal marker of identity, especially among literate elites, and was common by the 18th century. Still, in a mostly oral culture, signatures functioned more as ceremonial gestures than verification tools.

Heraldry and Livery

For the European upper classes, heraldry functioned as a visual shorthand for identity and lineage. Coats of arms adorned not only armor and flags but also furniture, buildings, and clothing. Retainers wore livery bearing their master’s symbols, making them recognizable on sight. Even death could not erase this symbolism—funerals were staged with heraldic banners, horses emblazoned with arms, and crests atop hearses.

Yet heraldry could also be diluted or faked. By the 16th century, unauthorized use of coats of arms was widespread, and forgers such as the Englishman William Dawkyns were arrested for selling false pedigrees and impersonating royal officers. In time, heraldry gradually lost its power to function as a reliable ID system.

Memory and Proximity

In the end, one of the most effective early methods of identification was simply being known. In rural communities, neighbors kept tabs on each other through personal memory and observation. You didn’t need a signature if the village priest or market vendor had known you since birth.

But with the rise of cities and the disruption of industrialization, such personal networks broke down. The state stepped in with systems of registration, documentation, and, eventually, visual records. Identity, once rooted in familiarity and the body, became a matter of paperwork and policy.

Before the photograph fixed the face in official form starting around the late 19th century, people relied on a more fluid, and sometimes fragile, constellation of signs: names, scars, clothing, crests, seals, and simple familiarity. All were attempts to answer the same eternal question—who are you?—in the absence of a camera’s eye.

Source: historyfacts.com

Contributed by Jane Hart